Myanmar: Temples and towers

Incredible temples range across Myanmar; from the magisterial Shwe Dagon in Yangon to Bagan’s sprawling complexes they show the country’s rich Buddhist art, culture and heritage. The monks often built them high up, as in Mandalay Hill, above. Sitting closer to God and above the everyday,as in many other religions, was a beneficial position for the builders of these incredible structures, but they are also a nice place to put the harbingers of modernity, cell phone towers. Now they often live together in the hills, symbols of the religion that defines much of the country’s culture and history alongside those of its looming future. One to talk to God, the other to talk to your fellow man.

Myanmar is a country on the verge of big changes. You can feel it in your conversations with almost anyone you meet. After over fifty years of dictatorship following a brief post-colonial interlude, the country’s people are starting to grasp the meaning of independence, democracy, and embracing the world. This is coming most vividly in the form of rapid cell phone adoption.

Telenor and Ooredoo

Ooredoo’s network goes live in Yangon, August 2014. Myint Lwin Oo/CNET

Last year, the government allowed two new foreign entrants into the national telecom sector, Norway’s Telenor and Qatar’s Ooredoo, to build out cell networks throughout the country. Less than two years ago SIM cards cost hundreds of dollars, Internet penetration rates were less than 1% and almost every piece of tech you bought needed to be government approval. Now, with the help of these new operators, Myanmar is moving rapidly to total coverage, because part of these companies’ contracts were to build all over, and quickly, in less than 5 years. Obviously this is also beneficial for the telcos, as well, more customers, connections and ubiquitous cell phone signals. Now you can’t go a block in the big cities such as Yangon and Mandalay without seeing an Ooredoo billboard, a Telenor cell phone shop or a corner market offering SIM cards for both alongside of the Myanmar Post and Telecom’s fading facades.

This plan is now backed by a government that has profited for years on a total lack of information in any facet of life. In a country with a literacy rate of over 90% it fed the population a diet of propaganda and gave them little opportunity to improve their perspective, whether through newspapers, the Internet or other media. There was no domestic Internet, partly because a lack of development led to problems establishing a standard Burmese script

online, and few people had the money, technology, connections or skills to use a browser or email to find information online. This is generally still the case for a majority of the population.

Where Facebook is the Internet and Gmail is Email

This has skewed an entire population’s perspective and experience in terms of their information or digital literacy, basically their understanding of the technology, Internet, and information that is presented to them in any form and through various media. In developed countries, we have struggled for years to integrate all of these new devices and services into our daily routines, but were given years to do this and often still wrestle with the daily deluge of data, email, new social media networks and a thousand other IT problems. They now are getting all of this at once, alongside the institution of new democratic systems.

The result is often confusion. Americans may remember their own struggles to venture outside of AOL’s walled garden into the wilds of the World Wide Web, Myanmar’s people have the same troubles breaking outside of Facebook’s boundaries. Zuckerburg’s machine is one of the few large web companies to have adopted the flawed but widely adopted Zawgyi font, which does not conform to Unicode standards, a problematic conflict for anyone trying to make a search or use a keyboard in any consistent fashion. Facebook has captured the market through text in the

flawed but widely used code while Microsoft, Google and others wait for Unicode implementation. At the same time, Facebook Zero offers new cell phone users a month of free access, with general word of mouth and online virality, the blue wave has totally saturated the country.

I saw prices anywhere from three to seven thousand kyat (three to seven dollars) just to set up an account on the streets, and many people who know nothing about the Internet know everything about Facebook and desperately want it. However when you ask them if they use or want other services they are generally uncertain. Viber is popular and Gmail is the only email most people send because Android is the most widely used operating system by far.

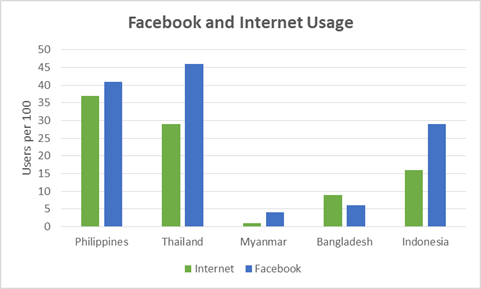

Source: LiRNE Asia

A recent article by Quartz magazine backs up earlier data about Myanmar, Indonesia, Nigeria and other developing countries with recent technology adoption. Researchers at the Sri Lankan NGO LiRNE Asia found that 47 percent of Thais had used Facebook, but less than thirty used the Internet, 29 and 16 percent of Indonesians, while in Myanmar less than 1% of people used the Internet but just over four out of every hundred were on Facebook in 2012. Not only is Facebook the most popular information resource, in many cases Facebook is the Internet.

An IT Conference without the T

Barcamp, or how to get ahead in information communication technology.

So this made one of Southeast Asia’s largest “Barcamps” an interesting experience. What would people talk about at a technology conference in a place where very few people can see beyond the cell phone, the blue social network, and were previously prohibited from looking beyond the government spokesperson or neighbor they trusted. This is a picture of a keynote address on how to do a job interview. Notice that no one has a laptop, very few have tablets, but a full house of people are all intently listening to someone talk about how to find work in the IT industry on the campus of one of the largest incubators of Myanmar’s tech community in Yangon.

Throughout courses on application development, cybersecurity or even witchcraft, few of which I understood except through the slides, (often in English) the audience sat transfixed throughout a variety of conversations. Many of the subjects would be completely new to the listeners, others were just beginning to understand the online world they are just getting into.

The Digital Teahouse

A teahouse in Yangon, speakeasy?

Many teahouses and cafés now sport Telenor or Ooredoo umbrellas, and it is not surprising, because these have been Myanmar’s center of conversations throughout years of empire and dictatorship, and well before. During the years of the junta, from 1962 until a few years ago, these were the places where whispers spread, before the internet, before democracy, before the world came crashing in. These social networks fortified people through years of poverty and struggle, and now these teahouses are starting to spring online. What will they say about the new democracy, with elections this fall, and where will they say it?

Probably Facebook, Viber, or Gmail or any number of places down the line, starting with the largest social network in the world, but they are moving into the digital realm we already inhabit everywhere else. How they will get there, and how it will transform their society along with economic development, reopening and democratization? How these

social networks will operate and who decides on how they run is up to the government, multinationals, a nascent private sector and civil society. As they adapt to these realities, both at local and high levels, this is becoming a complete informational as well as political and economic revolution.

This blog post, written by Dan Arnaudo on his blog ipolitico, was reposted here with his permission. Dan is currently working on TASCHA’s Information Strategies for Societies in Transition project.